How to Treat Your Dying Corals

- Aug 18, 2022

- Anshika Mishra

- 249 0 0

Sometimes, things don't go the way we like. Sometimes corals can show signs of stress or even die. But as long as you are prepared and know what to do beforehand, that part of the journey can be a bump in the road. There is something satisfying about spotting a problem, instinctively knowing what to do, and implementing the right action all that's coming up:

Unless you follow all the best practices perfectly, the chances are almost everyone will run into a phase where the corals don't look so great. Maybe even lose some tissues and die. But, simply knowing what to do is one of the challenges here, and we're going to beat it.

The primary reasons behind sick and drying corals are:

- Water parameters

- Lighting

- Water Quality

- Pests

Water Parameters

This is causing a variety of corals to be all showing issues at the same time. There are four parameters to look at, and they matter in this order:

Salinity

When salinity is off, everything is off. We are looking for 35 parts per thousand, and if it's slightly off, you probably won't see an immediate major issue. In either case, it should is fixed once noticed.

Reducing salinity is just removing saltwater from the tank and replacing it with fresh RO/DI water. Increasing salinity, add some saltwater to the tank, and let the excess water evaporate off.

A series of more significant water changes might be the best solution for more significant increases where salinity is way under.

Alkalinity

This is the most important single parameter. If you maintain stable alkalinity, you'll be a hundred times more successful if you don't

Calcium and Magensium

It is still essential but to lesser degree magnesium.

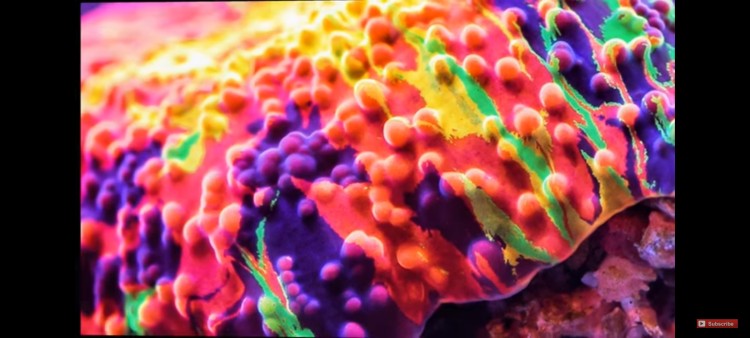

Lighting

Suppose you run into issues right when you had an otherwise healthy coral, and everything else looks great. There's a high likelihood that it is due to lighting or the PAR is too high for that coral.

Too much light is toxic to coral and can kill it in a matter of days. Or not enough light might take weeks to show signs of distress and months to die.

Corals receiving too much might shrink up, retract polyps, bleach white, or close, and often lose tissues. If this happens to a newer coral addition, move it to a lower light area of the tank. Then, like the sides or bottom, give it many weeks to recover before moving it again.

If this happens after you add the first batch or coral or make a setting adjustment to your lighting, turn the lights down. Just remember that sliders are not a toy. This is life support for organisms that depends on you.

Corals can adapt to most lighting simply as long as you leave them alone after. So every week, you can be considered an immediate setback with only a chance at improvement over the long run.

Water Quality

Either from slow deterioration of water quality from less than stellar feeding or maintenance practices or unintentional contaminants.

To identify this, start looking at nitrate and phosphate levels; if they are sky high, they may cause stress. But more so, just a general indication of low-quality polluted water.

Most first-year reefers shoot for a few parts per million nitrate and then a few tenths of a point phosphate in the new tank. However, nitrate can be found at ten or so parts per million in an established tank where algae are less of a threat.

If you post that feeding filtration rises above twenty parts per million, it might be this reason.

The bucket test is also something you can consider. Put a bucket of water from your tank next to freshly mixed saltwater, and you'll be able to see if the water is polluted visibly.

It doesn't need to be perfect, but tests like these are solid pulses on water quality. There are also un-intended pollutions that can cause issues. Like lotions, oil soaps, or other residues on your hands.

Do 30% water changes a few days apart and turn over most of the water in the tank. If you suspect a particular harmful accidental contaminant and things are dire and rapidly deteriorating, with hardy corals, 50-90% water changes are better than letting things deteriorate further.

If water changes solve your issue, it's time to look at the general maintenance practices and potential pollutants.

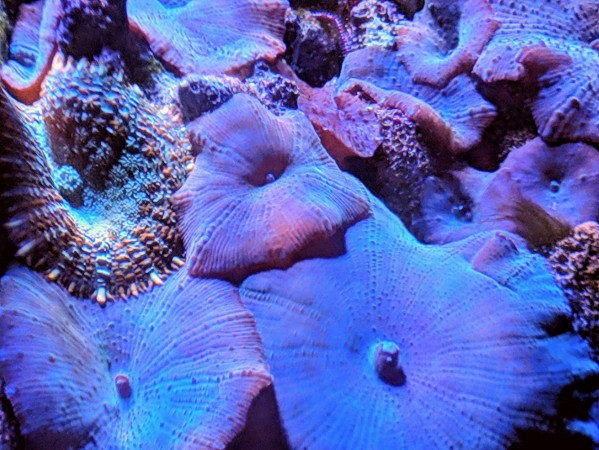

Pest, Fungus, or Infection

These things often only affect a single coral or a type of coral. In this case, it's time to take a coral out and dip it.

Do the dip and then look closely at the water left in the water. If you suspect a fungus or microbial infection, use iodine-based drops.

In some corals, you can also cut off the diseased portion. That'll often stop the progression right there.

About author